Background: Variations in Seasonal Water Relations of Four Gymnosperm Tree Species in a Snowpack-Dependent Ecosystem

Why Turgor Loss Point?

Understanding plant hydraulic traits and cellular water relations is essential to predicting tree persistence. A maintained minimum turgor pressure is an important constraint to the cell division process: when turgor pressure gets too low, the cell wall ruptures, cellular death occurs, and the leaf is left compromised, leading to potential senescence. (Read more below)

This study aimed to both measure species’ levels of isohydry and to measure how much Turgor Loss Point varies throughout the growing season

Further Information

What is Turgor Loss Point?

“If turgor is lost, stomata can close, plant cell metabolic processes can decline, and, if water potentials are severe enough, cell walls can collapse and cells can undergo plasmolysis and become metabolically inactive”

(Taiz, Zeiger, Møller, & Murphy, 2015)

Leaf cellular turgor is an important component of leaf structure and function. Understanding how these hydraulic traits are managed throughout a day, and the season, can give further insight into how plants maintain water status under stress. This has implications for future distribution modeling in a changing world.

How to find Turgor Loss Point by Pressure-Volume Curve:

Why Hydraulic Traits Matter

Understanding Plant Hydraulic Traits is essential: Hydraulic traits are thought to be the leading predictors of plant mortality due to drought

(Anderegg et al., 2016)

A study on drought experienced by pinyon-juniper woodlands in New Mexico measured the iso/aniso-hydric abilities of these species, and saw severe mortality in the Pinyon pines due to drought and an associated bark beetle outbreak. It is hypothesized that the difference in the water use strategies of the Pinyon pine and juniper greatly affected the trees’ ability to persist and survive post-drought. (Craig Allen, 2002)

Iso/aniso-hydry

The extent to which a plant limits water loss can be characterized along a spectrum ranging from extreme isohydry to extreme anisohydry. This characterization was first described in 1998 by Tardieu et. al. Isohydric plants conserve minimum water potential under times of reduced moisture by closing their stomata, while anisohydric plants prioritize the ability to fix carbon and risk their hydraulic safety. The determination of where a plant falls on this iso/aniso-hydric spectrum can be achieved by examining its “hydroscape,” which is the range of water potentials observed during a dry-down period.

Recent studies have aimed to quantify and characterize the stomatal control and minimum water potential a plant experiences throughout a dry-down- usually quantified as a hydroscape. These characterizations are new, and since the proposal of the idea of hydroscapes, the focus has been on methodology behind hydroscape calculations. Little research has focused on the relationship between this iso-/aniso-hydry and a tree’s leaf cellular water relations.

Iso/aniso-hydry and E (evapotranspiration) Trends

(Hochberg, et al. 2018)

The Study Site/Western United States

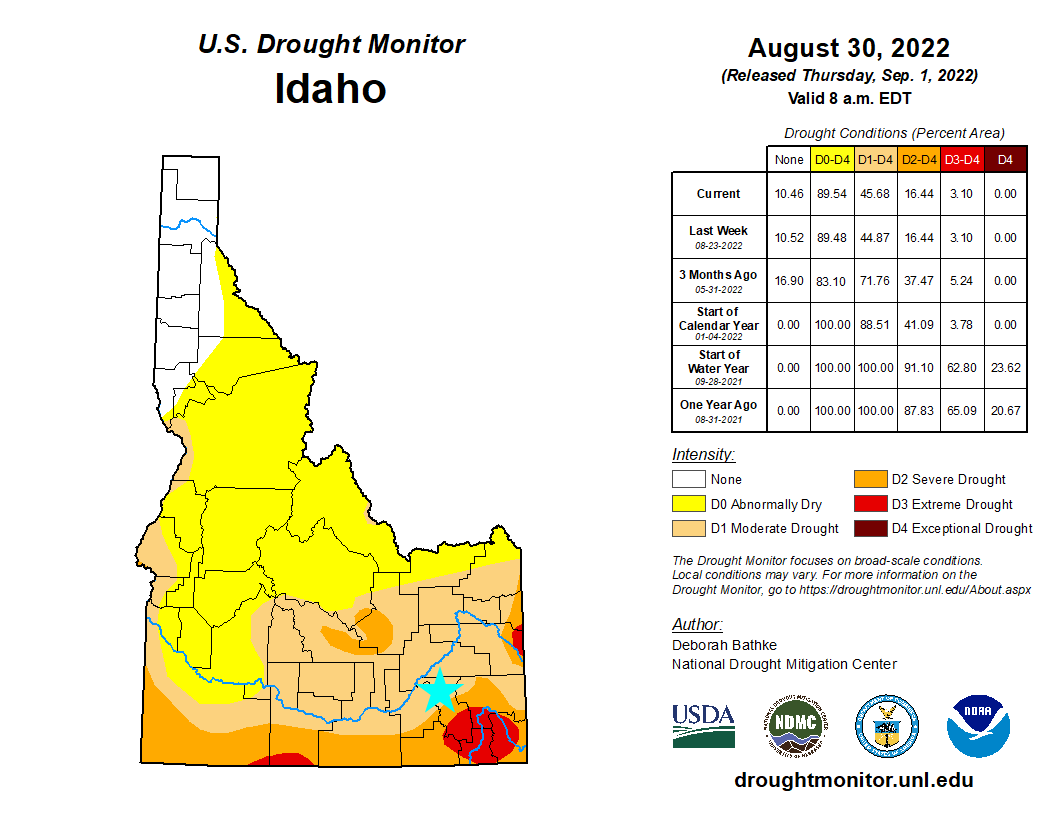

The study site was located in the Northern Basin and Range region (southeast Idaho) at the East Fork Mink Creek Nordic Center, part of the Caribou-Targhee National Forest near Pocatello, Idaho (42.714025°N, -112.377262°W & 42.721781°N, -112.379429°N). The study site is classified as primarily a “High Elevation Forests and Shrublands” ecosystem (ecoregion 80c, as defined by the EPA ), and was surrounded by “Semiarid Hills and Low Mountains” ecosystems (ecoregion 80b, defined by the EPA). This area is characterized by its mix of sagebrush grassland, mountain brush, and a mixture of conifers (particularly on north-facing slopes).

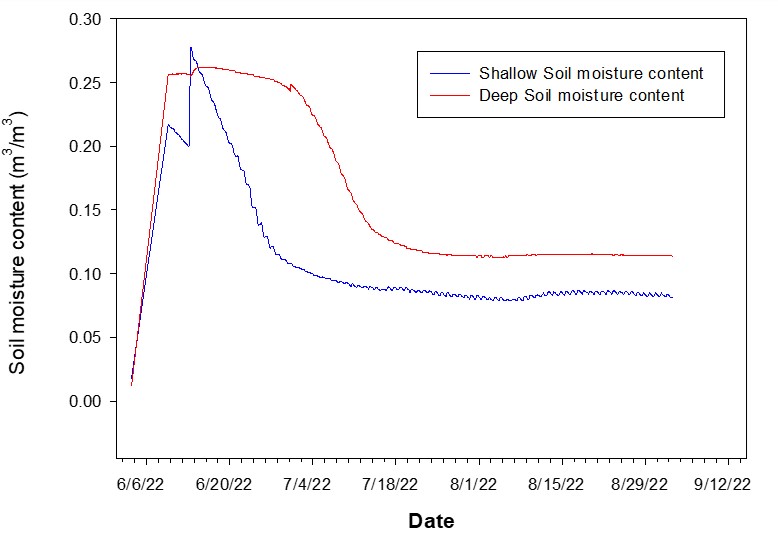

The soils in this region are described as type 307 Lanoak family-Robin complex, with 10-35 percent slopes (USDA). A previous survey of the area found that most of the soil at this site is silt-loam down to approximately 27 inches, where there may be the addition of clay (USDA ). The elevation is between 5,180 to 6,200 feet, has a mean annual air temperature of 33-43 degrees F, and an annual precipitation of 25 to 29 inches (primarily occurring in the winter as snow-pack) (USDA).

Related Studies

“Leaf hydraulic parameters are more plastic in species that experience a wider range of leaf water potentials” Johnson et al., 2017

My research approach was similar to this project, which also examined Turgor Loss Point and iso/aniso-hydry. This project found that isohydric species alter their turgor loss point throughout the growth season less than the anisohydric species that cohabitated that ecosystem

References

-Johnson, D. M., Berry, Z. C., Baker, K. V., Smith, D. D., McCulloh, K. A., & Domec, J. (2018). Leaf hydraulic parameters are more plastic in species that experience a wider range of leaf water potentials. Functional Ecology, 32(4), 894–903. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13049

-Meinzer, F.C., Woodruff, D.R., Marias, D.E., McCulloh, K.A. and Sevanto, S., 2014. Dynamics of leaf water relations components in co‐occurring iso‐and anisohydric conifer species. Plant, Cell & Environment, 37(11), pp.2577-2586.

-Meinzer, F.C., Sharifi, M.R., Nilsen, E.T. and Rundel, P.W., 1988. Effects of manipulation of water and nitrogen regime on the water relations of the desert shrub Larrea tridentata. Oecologia, pp.480-486.

-Taiz, L., Zeiger, E., Møller, I. M., & Murphy, A. (2015). Plant physiology and development. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Incorporated.

-Tardieu, F., & Simonneau, T. (1998). Variability among species of stomatalcontrol under fluctuating soil water status and evaporative demand:Modelling isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. Journal of ExperimentalBotany, 49, 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/49.Special_Issue.419